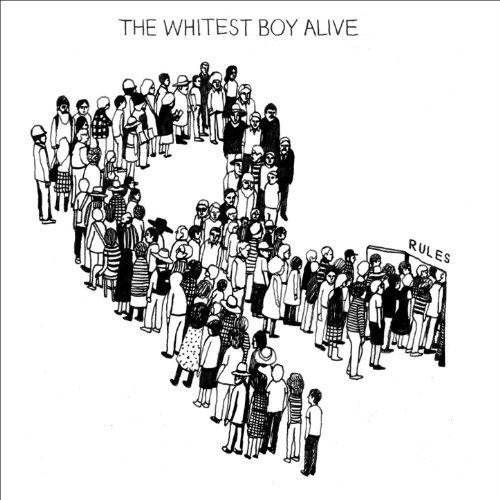

The Whitest Boy Alive

Rules

Release Date: Mar 31, 2009

Genre(s): Indie, Rock, Dance, Alternative

Record label: Bubbles

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy Rules from Amazon

Album Review: Rules by The Whitest Boy Alive

Satisfactory, Based on 7 Critics

Based on rating 7/10

By now some may be frustrated with Erlend Øye’s refusal to expand his vocal horizons. The Norwegian singer has moved from folk to electronic, but whatever genre he tackles, he maintains that same effortlessly smooth, refrained and detached voice. However, while some may find Øye’s voice clinical, it is also what makes his projects so unique; the music and the vocals blend together to produce one smooth, singular, wistfully daydreaming expression.

Based on rating 7.0/10

Erlend Øye formed the Whitest Boy Alive with the intention of taking a break from Kings of Convenience's restrained acoustic sound and making electronic dance music. But the group's first album, 2006's Dreams, fell far short of the electronic mark, sounding a lot like a plugged-in Kings of Convenience with a rhythm section. Dreams' catchy, indie-pop tunes seemed designed to get shy kids shaking in their bedrooms rather than to set dance floors on fire.

Based on rating 6.3/10

One of my favorite singles last year was Fred Falke's remix of the Whitest Boy Alive's "Golden Cage", a glossy, euphoric piece of electro-pop that mutated a gentle, unassuming disco comedown into a late-decade bookend to Daft Punk's "Digital Love". Yet despite the way Falke's remix brought out the best qualities of his syrupy, lonesome voice, Whitest Boy (and Kings of Convenience) head Erlend Øye is most comfortable when he's a bit subdued and quiet. And as much as massive house beats complement his vocals, he seems most at home when his musical surroundings undergo the same state of half-withdrawn restraint that he's in.

Based on rating 5/10

Erlend Øye was responsible for a couple of the more quietly influential releases of the early 2000s -- the Kings of Convenience's wispily gentle, prophetically titled debut Quiet Is the New Loud and his affable, microhouse-popularizing DJ-Kicks set, not to mention his fine vocal contributions to Röyksopp's early singles -- all thoroughly excellent if hardly earth-shattering work. In the latter part of the decade, though, his output and impact seemed sadly diminished as he lapsed into a middling, milquetoast groove as frontman for the smooth pop outfit the Whitest Boy Alive. The group's second outing is, like everything Øye touches, never less than pleasant, poppy, and unfailingly polite.

Based on rating 5/10

The Whitest Boy Alive’s Erlend Øye is a man blessed with good taste; the kind that often serves as a bellwether of things to come. When he first popped onto the radar in 2001 as part of Kings of Convenience, Øye and musical partner Eirik Glambek Bøe anticipated the return of folk with a sound that saluted the chamber pop and folk stars of yesteryear. The duo even presciently named their debut Quiet is the New Loud – a concept only truly validated by the phenomenal success of Fleet Foxes and Bon Iver in 2008.

Based on rating 2/5

Erlend Oye, a spectacle-wearing redhead from Bergen with a faint, fragile voice, is one of Norway's unlikeliest pop stars. When he was one half of indie band Kings of Convenience, his devastating gentleness made sense, but this style has never really gelled with the dance music he has made as the Whitest Boy Alive. This is his second album under that name, and one assumes that Oye fancies it as a simple, textured piece of modernist art.

Opinion: Very Good

Something’s not right here: Rules either grooves more than an introspective album is supposed to or introspects more than a groove album is supposed to. It’s all sleekness and shuffle on the way down, and all eloquent discomfiture inside; it sounds like lounge music that narrates the lives and loves of people who are terribly embarrassed by the idea of setting foot inside a lounge. As paradoxes go this is all pretty tame, but in the hands of Erlend Øye, who brought us “quiet is the new loud” at the beginning of the decade, it feels like something of great consequence, as though a whole generation’s sense of self hangs in the balance.

'Rules'

is available now