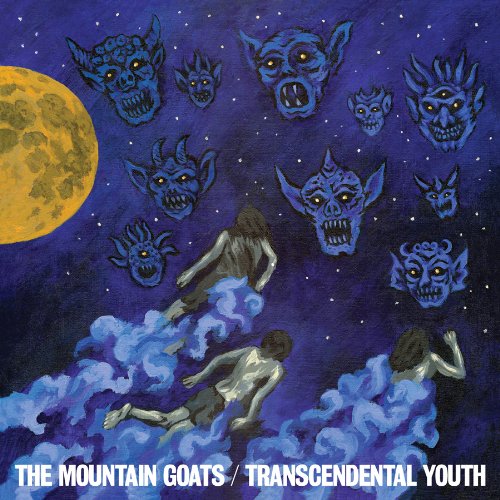

The Mountain Goats

Transcendental Youth

Release Date: Oct 2, 2012

Genre(s): Alternative/Indie Rock, Alternative Pop/Rock, Indie Rock, Lo-Fi, Alternative Singer/Songwriter

Record label: Merge

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy Transcendental Youth from Amazon

Album Review: Transcendental Youth by The Mountain Goats

Excellent, Based on 21 Critics

Based on rating 5/5

An album full of characters struggling against dead-end jobs, drug addiction and depression doesn't exactly sound inviting, but in the hands of John Darnielle, it's magic. Darnielle is a former psychiatric nurse; his catchy, gracefully appointed chamber-pop songs paint portraits of dread and paranoia with empathy and precision. "Harlem Roulette" – which jump-cuts from Frankie Lymon's final recording session, in 1968, to the 21st-century Pacific Northwest – is as close as a pop song gets to philosophy.

Based on rating 4.5/5

Review Summary: We shall all be...You like to think that you’ll have it figured out by the time you die, that surely nobody can live for so long without learning the secret or whether there even is one. You think maybe you’re missing out on some crucial parts of life because you can’t stop thinking of how it will end, but you also think that those crucial parts won’t be so crucial without knowing what they add up to. And every day you seem to get farther and farther away from the answers.So you listen to The Mountain Goats.You listen to the horns and the lovely vocal harmonizing, and you know the weight you feel will never lighten, but you also know that it will become easier to bear.

Based on rating 83%%

John Darnielle has been making music for a long time. Not all of it has been readily accessible or approachable, but the last few releases under The Mountain Goats moniker have been more in line with what one thinks of as a “rock” record. Joined by bassist Peter Hughes and Superchunk drummer Jon Wurster, Darnielle’s brilliant, pointed lyrics are reaching a new audience.

Based on rating 4/5

It seemed, on the surface, that John Darnielle’s “Satan record,” Transcendental Youth, would be inimical to my Christian sensibilities. In church, I was taught from a young age to fear Satan. Growing up, I was warned in school and in church to fear “Satanists” and their covert influence in “the media,” government, and, especially, in any fun and/or enjoyable thing — especially music.

Based on rating 4/5

Don’t let the “concept” fool you, because when John Darnielle says the album loosely revolves around a struggling outcasts from Washington, that doesn’t explain how we get to Frankie Lymon’s final recording sessions in “Harlem Roulette,” or the disarmingly lucid schizophrenic hunting down “Counterfeit Florida Plates” from the grates he sleeps on, certainly not the Scarface rejoinder “Diaz Brothers” and frankly I bet lots of non-Seattle apartment complexes are called “Lakeside View. ” Whether Darnielle’s trying to con us (comeback album?) or himself (14 word-stuffed albums in, ambitions slowing down is hardly to be ashamed of), he has reached the stage where the canon is established and being responded to. What a run: from the lo-fi treasure trove that culminated in 2002’s plenty triumphant All Hail West Texas (I hear longtime fans love Zopilote Machine but I prefer Nine Black Poppies myself) to the trilogy of concept albums best-acclaimed by the cult of critics who began to recognize the now-more-than-one-man-band as a character-loving wordsmith akin to the Hold Steady or Drive-By Truckers.

Based on rating 8/10

At least since the outwardly autobiographical The Sunset Tree, if not earlier, what’s emerged as the major theme of John Darnielle’s songwriting is the collective stories of downtrodden/outcast/ignored/abused people struggling to survive amidst the pain, memories and demons haunting them. That theme is more in the open these days, coinciding with the group’s continued musical clarification – an increasing unity of purpose and sound – and with Darnielle’s more direct explanations about what his songs are about. The musician who once cut an email interview with me short after evading my (too) many “what is this song about?” questions now does stage banter relating that, for example, a particular song is about him losing his virginity.

Based on rating 8/10

Repeating that this is the SIXTEENTH(!) Mountain Goats album isn’t necessarily going to convince swing voters – 'oh well, if they’ve made 16, I suppose it’s time to give them a try…' but what gave me pause for thought is that it’s been ten years since John Darnielle graduated to the indie premiere league, with Tallahassee (2002), on 4AD. A few people who were at their peak then, documenting extremes of the human condition in symbolic language, are on indefinite hiatus now, including David Berman, Jason Molina, and David Foster Wallace (rapidly becoming the Kurt Cobain of postmodernism). Transcendental Youth therefore begs the question: what does it take to go on? In the mid-to-late-Nineties, when lo-fi was loosely defined by Smog, Silver Jews, Sebadoh, and GbV, The Mountain Goats cropped up as the band who '…if you really like that sound, try this…' ‘This’ being: a guy yelping at his boombox as he battered an acoustic guitar, more percussively than anything else.

Based on rating 8/10

Songwriter John Darnielle has been one of the more prolific figures in indie rock, turning out album after album of his melodically wistful tunes under the Mountain Goats moniker since he started with poorly recorded cassette albums in the early '90s. Transcendental Youth is the 14th proper Mountain Goats album, and it's a dark ride, seeing Darnielle return to the depressive character studies and possibly autobiographical bleak tales that made up some of his most striking work. Beginning with the strident and almost bounding "Amy aka Spent Gladiator 1," all of the trademark elements of a Mountain Goats album fall immediately into place: Darnielle's wiry personality and sometimes breathless voice, quickly transitioning pop song structures, and lyrics that shift from humorous to dire in the space of a line or two.

Based on rating 8.0/10

If freedom was just about having "nothing left to lose" for Kris Kristofferson, then for the Mountain Goats' John Darnielle freedom is more like having nothing left to tear to the ground. The characters in Darnielle's songs have long been the architects of their own destructive freedoms for better or (often) worse. As the poet laureate of the down and out, Darnielle has constructed countless narratives of the rock-bottom, often mixing zeal and depravity in equal measures, crafting hope out of hopeless situations, looking at the cinders of lives lived through scorched-earth policies as the embers of a new beginning.

Based on rating 7.8/10

In the introduction to Tiny Beautiful Things, a collection of Cheryl Strayed's advice columns, the writer Steve Almond uses the term "radical empathy. " I underlined it and wrote in the margins of the book "John Darnielle. " I cannot think of two words that better sum up the strange powers that the Mountain Goats frontman has spent two decades and a small shelf's worth of LPs tirelessly honing.

Based on rating 77%%

The Mountain GoatsTranscendental Youth[Merge; 2012]By Chris Bosman; October 4, 2012Purchase at: Insound (Vinyl) | Amazon (MP3 & CD) | iTunes | MOGJohn Darnielle isn't just talking anymore. It's been ten years since Darnielle took his Mountain Goats project to 4AD and began fleshing out his sound beyond the hyper verbose four track recordings of his earlier output. But even as recently as his Merge debut All Eternals Deck, it's been the words that litter any Mountain Goats record that have garnered the most attention.

Based on rating 7.5/10

Mountain Goats frontman John Darnielle has a new baby, but that hasn’t softened his love for dark subject matter. (“Please,” he wrote on his website in July. “May the baby grow up to spit in my face if I should pose that hard.”) Transcendental Youth, despite its frequent use of a punchy horn section, is bleak, even by Darnielle’s standards.

Based on rating B

Few artists are as prolific as The Mountain Goats’ John Darnielle. Where others might have prodigious stretches, Darnielle’s in it for the long haul: the famously dyspeptic songwriter’s output is up to a staggering 14 albums by this, the band’s 18th year of existence. Though his music is best known for addressing heartbreak and self-destruction, Transcendental Youth finds Darnielle playing a new tune — happiness.

Based on rating 7.2/10

John Darnielle and his Mountain Goats have frequently been at their best while capturing characters in dark situations, usually struggling to get through. Darnielle’s direct lyrics can pinpoint an emotion without limiting the utility of sharing that experience. On Transcendental Youth, the band takes us through a series of trials, flickering a light in a pursuit of something more.

Based on rating 3.5/5

John Darnielle’s been doing his thing as The Mountain Goats for 21 years now, and his 14th album under that name is business as usual. We get stories about the sexual abuse of altar boys on ‘Cry For Judas’; Amy Winehouse, on ‘Amy (aka Spent Gladiator I)’; and a couple of drug dealers who are briefly mentioned in Scarface, on ‘Diaz Brothers’. It’s the kind of stuff Darnielle’s whole career has been built on.

Based on rating 7/10

John Darnielle has come a long way from the hissing tape splinters on the earliest Mountain Goats records. That’s not to say that he, nor the band, has conceded to mainstream production demands on their last few records, but their recent albums have definitely sounded better than any in their pre-Tallahassee period. The fact is that the churning analog rawness which figured so prominently in those early albums was a large part of the reason why fans gravitated towards the band.

Based on rating 3.5/5

In a 1978 Good Morning America interview, Pete Townshend offered a neat summation of the therapeutic benefits of rock n’ roll: “Rock music is important to people because in this crazy world it allows you not to run away from the problems…to face up to them, but at the same time to sort of dance all over them. That’s what rock n’ roll’s about. ” John Darnielle, who bills his prolific recording output as the work of a semi-real band known as the Mountain Goats, doesn’t always dance, but on Transcendental Youth he’s at least learned to shimmy, while his latest song cycle, in keeping with his usual m.

Opinion: Excellent

THE MOUNTAIN GOATS “Transcendental Youth”. (Merge).

Opinion: Excellent

Transcendence doesn’t come easy for the characters in John Darnielle’s songs. For over 20 years the songwriter has put together a murderer’s row of outcasts, speed-freaks, thieves, tortured musicians, washed-up actors, alcoholic stepfathers, paranoid science-fiction writers, Satan-worshippers, peanut-lovers and actual murderers. They’re often manic, depressive, manic-depressive or just plain desperate, and though Darnielle often catches them in their quieter, more reflective moments, they’re not the type of people one might associate with a spiritually gooey and Emersonian word like “transcendence.

Opinion: Very Good

If John Darnielle needed a slogan, look no further than "Do every stupid thing to drive the dark away" from 'Amy aka Spent Gladiator 1,' the first track from Transcendental Youth, his new album under the Mountain Goats moniker. Strumming an acoustic guitar ferociously enough to worry about the safety of the strings, he’s keeping darkness at bay one note at a time. In a career of apt album titles, this might be the best: Darnielle’s empathy for tweakers and stealers of sunscreen from CVS springs from a belief in youth as a state of continual stimulation, during which characters stumble from experiences that look like epiphanies when there’s a writer to record them.

Opinion: Average

In an age where the line between what constitutes ‘folk’ and everything else is blurred by the popular appeal of an ever-growing troupe of singers with beards and acoustic guitars, the identity of some long-standing musicians can drift in to the shadows and remain there. And when you’re releasing your fourteenth studio album, the concern of losing focus and direction is even more prevalent. Over the course of The Mountain Goats’ recordings their sound has progressed from lo-fi, rustic folk to a more polished - and dare I say it - generic sound.

'Transcendental Youth'

is available now