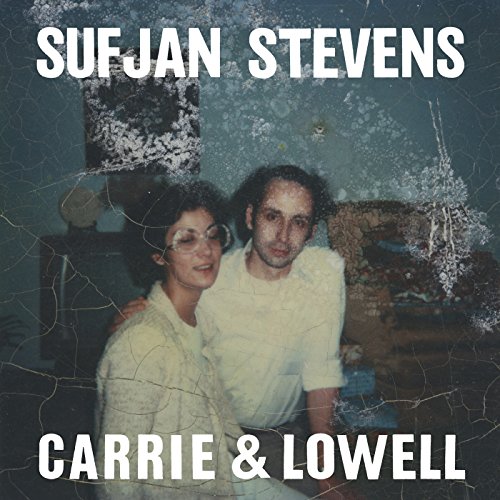

Sufjan Stevens

Carrie & Lowell

Release Date: Mar 31, 2015

Genre(s): Singer/Songwriter, Pop/Rock, Alternative/Indie Rock, Indie Rock, Lo-Fi, Indie Pop, Alternative Singer/Songwriter, Indie Folk, Chamber Pop

Record label: Asthmatic Kitty

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy Carrie & Lowell from Amazon

Album Review: Carrie & Lowell by Sufjan Stevens

Exceptionally Good, Based on 30 Critics

Based on rating 5/5

For all the plaudits that greeted Sufjan Stevens’ Michigan and Illinois albums, there was always the nagging feeling that his music was more involving and moving when it was less high-concept, as on Seven Swans. He returns to that mood – sombre and intimate, with sparse instrumentation – for his seventh album, on which heartbreak and death are intermingled. “Shall we beat this or celebrate it?/ You’re not one to talk things through,” he sings on the devastatingly beautiful All of Me Wants All of You, then follows that line, bitterly, with: “You checked your texts while I masturbated/ Manelich, I feel so used.

Based on rating 5.0/5

Review Summary: “This is not my art project. This is my life.”The moments that tear us down to practically nothing determine who we are. They strip us of what is comfortable and familiar while forcing us to draw strength from within. One of the harshest realities facing every human being is death, and that includes the occurrence itself as well as grappling with its implications.

Based on rating 9.5/10

Sufjan Stevens’ Carrie & Lowell is a hyper-specific recount of memories from Stevens’ childhood, and of the emotions that struck him following the death of his mother, whom he barely knew. And while the actual facts that the album is based on seem like they could provide a wealth of fertile ground to cultivate great art—and they do—there is also the possibility that the events could be too personal for listeners to relate to or to gain something of an understanding to apply to our own life. But that’s the thing about family: everyone has one.

Based on rating 9.5/10

Head here to submit your own review of this album. "Amethyst and flowers on the table / is it real or a fable?" Real or fable is a question that remains unanswered seven albums into the world of Sufjan Stevens. For all the stories woven around the John Wayne Gacys, Casimir Pulaskis, Abrahams, Men of Steel, all of the places like Michigan, Illinois(e), Chicago and the BQE that Stevens uses for his songs, there's also the sisters, brothers, friends, mother, father and lovers that he drops into his lyrics that have always hinted at personal stories to be told.

Based on rating A

The first six albums by Sufjan Stevens split open at their seams with wonder. You can hear the way he pronounces his choruses in all caps: “ALL THINGS GO!” he declares on “Chicago”; “THIS IS THE AGE OF ADZ, ETERNAL LIVING!” on “Age of Adz”. On his seventh album, Carrie & Lowell, Stevens struggles to keep his voice from breaking. No longer triumphant, he sounds ragged, hoarse, done for.

Based on rating 9.3/10

Sufjan Stevens' new album, Carrie & Lowell, is his best. This is a big claim, considering his career: 2003's Michigan, 2004's stripped-down Seven Swans, 2005's Illinois, and 2010's knotty electro-acoustic collection The Age of Adz. He's also had residencies at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, collaborated with rappers and the National, donned wings and paint-splattered dayglo costumes, and released Christmas albums.

Based on rating 9/10

Sufjan Stevens has made a career out of imagining the lives of others through the eyes of a documentarian, examining regional history with a clarity of vision which provides a deep understanding of his nonfictional subjects. His ode to the states of Michigan and Illinois avoided a didactic purpose, depicting seemingly small lives rendered in grandiose orchestra leanings. In between this massive undertaking lay one of his most earnest statements, Seven Swans, which lay bare the spiritual core of humanity with theological observations applied with virtuous tolerance.

Based on rating 4.5/5

Great loss often inspires great art: Lou Reed and John Cale’s Warhol tribute ‘Songs For Drella’, or Rufus Wainwright’s eulogy to his mother ‘All Days Are Night: Songs For Lulu’ for example. To this catalogue of sublime sadness we can now add Sufjan Stevens’ ‘Carrie & Lowell’, named after his stepfather and his depressive, alcoholic and schizophrenic mother, who abandoned her family when Sufjan was 12 months old. Following her death in December 2012, the 39-year-old Detroit songwriter decided to make his seventh album a stark exploration of their fractured relationship.

Based on rating 4.5

Sufjan Stevens has sometimes sounded so overwhelmed by the world that he has tried to capture all its wonder in each individual song he writes. From the opulence of Illinois to the obfuscating clutter of The Age Of Adz, his approach to arrangement has often been that more is more. Stevens is a talented arranger, but his best work has tended to be his most direct and spare.

Based on rating 9/10

Carrie & Lowell is an incredibly sad record. Listened to in a delicate state, its songs can be harrowing. A friend of mine was brought to tears upon hearing ‘No Shade in the Shadow of the Cross’ on the radio recently, and when I heard it played from start to finish in a crowded bar a couple of weeks ago the effect was jarring (not least because it hasn’t yet been released).

Based on rating 4.5/5

Sufjan Stevens has had one of the most eclectic and ambitious, almost manic, careers in contemporary independent music. He's written everything from a ballet score to a long-form symphony for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, and he's recorded more Christmas albums than Bing Crosby. All of which makes his latest album, Carrie & Lowell, something of a departure.

Based on rating 8.5/10

Sparse in the elaborate repertoire of Sufjan Stevens is an album born without a concept. Be it of the flittering “50 states project” (Michigan and Illinois), BAM-commissioned “programmatic tone poetry” (The BQE), B-sides/Christmas song collections or otherwise, very few Sufjan releases have slipped by without receiving their “concept album” branding. Carrie & Lowell, however—though driven largely by a few linked themes—is not a concept album.

Based on rating 4/5

The death of a loved one is perhaps the most traumatic event that can take place in a person’s life, and it affects different people in different ways. Some folks turn inward and back, replaying the relationship with the deceased to make sense of the regret and guilt that often accompanies such a loss. Others try to look beyond, grasping at fantasies and myths in an effort to escape the harshest truth that real life deals us: Everybody dies.

Based on rating 4/5

SUFJAN STEVENS treats his new songs like seances. They’re dreamy attempts to communicate with the dead — specifically his mother, who died in 2012. The Brooklyn-based artist has been open about his mother’s alcoholism and mental illness. She left the family when Stevens was just 1 year old ….

Based on rating 4/5

Ever the restless soul, Sufjan Stevens has, since the hysteric electro of his last album proper, 2010’s The Age Of Adz, released an album with his hip-hop flavoured supergroup (Sisyphus), co-written and toured a cosmic classical song-cycle, Planetarium, and released a second box set of Christmas songs. On first listen, the quiet, thoughtful Carrie & Lowell could be seen as a reaction to such grand scheming, yet over time it becomes clear that it may be Stevens’ most fully realised record to date. While in the past his concepts have been largely reliant on fiction and the retelling of history (Stevens’ background is in creative writing), by naming this record after his mother and stepfather he’s given the listener cause to believe there may be something more personal on the cards.

Based on rating 8/10

Following Sufjan Stevens’ discography up to this point has been a study in addition. More instruments, more and more esoteric references, more genre exercises. It’s been a decade since Stevens recorded a straightforward folk album, having kept busy with experimental electronic outings like 2010’s The Age of Adz, his 2009 symphony to The BQE, and an absurd amount of Christmas music.

Based on rating 4/5

The 2012 passing of Sufjan Stevens' estranged mother, Carrie, sparked an existential crisis in the 39-year-old singer-songwriter. Here, on his most emotionally draining album, he joins Nick Drake and Elliott Smith in the canon of artists who channel suicidal thoughts into impossibly pretty songs. Stevens strips his sound far enough to reveal his deepest anguish; neither the Disney-style orchestras of 2005's Illinois nor the synth-pop-as-craft-project of 2010's The Age of Adz peek through his acoustic fingerpicking and warm-milk voice.

Based on rating 8/10

Nothing truly prepares anyone for the loss of a parent. No matter how aware one may be about the realities of disease and death, no matter what their attitude about their mother or father, experiencing the passing of the person who brought them into this world hits hard and deep, and the survivors are left to come to terms with their pain in their own ways. Sufjan Stevens is a songwriter and a musician, so it should come as no surprise that in the wake of the death of his mother Carrie in 2012, his grief took the form of a collection of songs.

Based on rating 4/5

‘Carrie and Lowell’ sees Sufjan Stevens refine his music down to its essentials. There are no orchestral flourishes, no electronic embellishments; there aren’t even any drums. With tongue lodged firmly in cheek Stevens has even jokingly described the album as “easy listening”. The truth is it’s anything but.

Based on rating 4/5

In keeping with two of his previous albums, 2005’s Illinois and 2003’s Michigan, Sufjan Stevens’s first album proper in five years was nearly named Oregon, the state where the Brooklyn-based indie hero’s mother and stepfather – Carrie and Lowell – were based throughout Stevens’s childhood. Eugene, a mid-album track named for Oregon’s capital, lists long-ago sense impressions – lemon yoghurt, dropping an ashtray on the floor, and a swimming coach who called Sufjan “Subaru”. On Should Have Known Better, Stevens remembers being forgotten at a video store, aged “three, maybe four”.

Based on rating 8/10

When Sufjan Stevens released Seven Swans in 2004, it was unfairly met with apathy by a Fifty States Project-starved listenership waiting for a follow-up to Michigan and somehow disappointed by the straightforwardly pretty album he offered up instead. But with the States Project now a distant memory and a five-year wait since his grandiose Age of Adz, perhaps people will listen to the subdued, melancholic beauty of Carrie & Lowell with different ears. It's a quietly triumphant return for Stevens, announced not by fireworks but by a series of small, elegant moments that reach for the heart.

Based on rating 3.5/5

Sufjan Stevens has always been one of the most eclectic yet profound storytellers of the past decade to me. Illinois is just one example of this. As with the rest of his work, he lays everything on the line here on Carrie & Lowell, named after his late mother and stepfather, respectively. While he's always braved it in terms of musical style, experimenting with either electronica or hip-hop upbeats, he dials things back here and channels his roots.

Based on rating 6/10

“Should I tear my eyes out now?” Sufjan Stevens wonders, his voice high and taut with pain, on “The Only Thing”, the seventh track of his seventh album, Carrie & Lowell. “Everything I see returns to you somehow.” That’s the nature of grief: relentless, all-consuming, and brutal. It’s a shadow that follows you around and darkens every joy.

Opinion: Absolutly essential

opinion byZACHARY BERNSTEIN < @znbernstein > “Is it real or a fable?” Sufjan Stevens muses on the benedictory “Death With Dignity,” the opening track from his seventh proper studio album Carrie & Lowell. Fans of Stevens’ work have been asking that same question for years. His 2005 magnum opus Illinois and 2003’s similarly conceived Michigan were stunning works of storytelling and musicality – vivacious syntheses of distinctly American narratives with lushly orchestrated folk, jazz, and indie pop.

Opinion: Fantastic

"Somewhere in the desert there's a forest/ And an acre before us/ But I don't know where to begin" ('Death With Dignity') For someone such as Sufjan Stevens, opening an album with a declaration of abandonment feels strange. It's uncharacteristic of a man whose previous records have been expansive, often jubilant tours de force of multi-instrumentalism, tracing lyrical lines through Biblical stories and American history, with tracklistings often running to the late teens; the work of a musician who knew, it seems, where to begin. But then Carrie & Lowell is an uncharacteristic record, one which doesn't follow Stevens' trajectory of taking a sonic departure from what's come before, instead returning to the plaintive folk of his earliest records as a vehicle for words that, for the most part, jettison allusion for bracing honesty.

Opinion: Fantastic

Twang sounds the way dust moves. It’s when curtains get pulled and light starts to shimmer where it shouldn’t; it curls out of place the way the dead float through your room, peacefully and invisibly. I do not think that’s what it used to sound like, but Sufjan Stevens has made a lilting, forceless companion out of it, a reason to open your eyes and then roll your head back onto the pillow.

Opinion: Excellent

A hushed, intent Sufjan Stevens contemplates death, grief, family and memory on his quietly moving new album, “Carrie & Lowell,” in songs that entwine autobiography and archetype. The music is restrained and meticulous, all graceful melodies, plucked strings and shimmery keyboard tones. But ungovernable circumstances and emotions course through the lyrics.

Opinion: Excellent

Some albums turn so far inward that you almost feel guilty when you hear them. It’s akin to eavesdropping on the artist’s inner thoughts and memories. Plenty come to mind: John Lennon’s “Plastic Ono Band,” Joni Mitchell’s “Blue,” Mickey Newbury’s “Looks Like Rain,” and Peggy Lee’s “Norma Deloris Egstrom From Jamestown, North Dakota.” Add to that any number of records by Elliott Smith, Billie Holiday, Nick Drake, and so on.

Opinion: Excellent

Brooklyn indie folk icon Sufjan Stevens has written albums about geography, history and myths, but on his newest he turns inward to sing about his mother and stepfather. It's easily his most personal work yet, and even though the story of his mother's difficult life is hardly universal, the results are deeply moving and richly evocative. The arrangements are sparser and more intimate than on previous offerings, mostly built around acoustic guitar, piano and layers of vocals.

Opinion: Absolutly essential

At the end of Carrie & Lowell’s best song—when the gorgeous, gutting “John My Beloved” is already over, really—Sufjan Stevens draws in a sharp breath. It’s a moment he didn’t need to leave in, but it speaks to the mood of his brilliant, stripped-bare seventh album: It sounds almost like the singer is overwhelmed by his own emotion, enough that he has to physically pull away. Maybe by including it he’s offering everyone else a chance to catch a big breath, too—which may be required for a collection of songs this simultaneously fraught and beautiful.

'Carrie & Lowell'

is available now