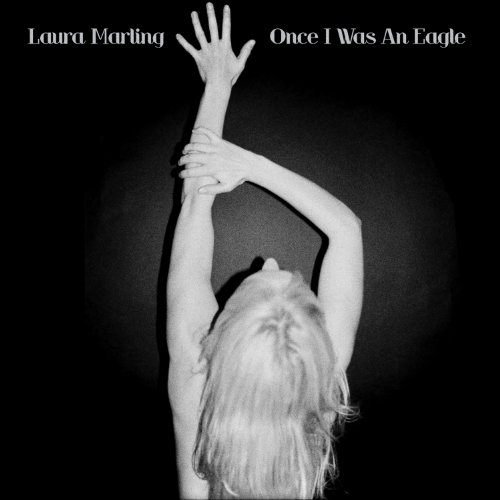

Laura Marling

Once I Was an Eagle

Release Date: May 28, 2013

Genre(s): Folk, Pop/Rock, Alternative/Indie Rock, Alternative Pop/Rock, Alternative Singer/Songwriter, Indie Folk

Record label: Ribbon Music

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy Once I Was an Eagle from Amazon

Album Review: Once I Was an Eagle by Laura Marling

Excellent, Based on 26 Critics

Based on rating 5/5

When Laura Marling announced that her follow-up to 2011’s A Creature I Don’t Know would be a mostly solo acoustic affair, one may have been forgiven for expecting a back-to-basics approach. As it happens, Once I Was An Eagle represents a bold, adventurous step forward that’s resulted in her most fulfilling work yet. Thrillingly, it begins with a seven-song, near-half-hour-investigating long suite which takes in late-night singer-songwriter fare, nods to devotional raga and, in Devil’s Resting Place, a tempestuous ending.

Based on rating 9/10

At 23 years of age, Laura Marling has released four albums, and each is better than the last. Don’t misunderstand: If you want to hear Laura Marling’s best songs, look elsewhere, specifically to 2011’s A Creature I Don’t Know. But if you want to hear a songwriter truly come into her own, change up the game, and unleash one of the most rewarding and promising folk albums—or rather, Album, with a capital A—since the heyday of the usual name-checks, it’s hard to call anything other than Once I Was An Eagle her best.

Based on rating 9/10

According to European folklore, Undine (or, sometimes, “Ondine”) is a water nymph fated to lose her immortality and gain a soul when she falls in love with a man. Depending on the version of the story, the mortal Undine is stripped of her rebellious nature and becomes a devoted wife, or is cheated on by her husband and curses him to eternal wakefulness, or is forsaken by her husband, embraces him until he dies, and forever encircles him as a magical spring. The turning point on Laura Marling’s fourth album comes with a plea for Undine to “make me more naïve”.

Based on rating 4.5/5

Laura Marling just might be an angel, or the closest thing that contemporary music has to one. If you watch footage of her live concerts, whether taking place in a field, a cathedral, or an intimate pub, you'll see a throng of rapt devotees, their faces as placid and focused as those of pilgrims, the occasional mouth shaping a lyric. Gracing the stage is Marling's almost preternaturally composed figure, staring straight ahead under pale bangs while deftly fingerpicking through a complex, multivalent composition.

Based on rating 4.5/5

Back in what now feels like the mists of time (let’s call it five years ago), before you could buy ‘artisan lifestyle’ pantaloons inspired by Ted Dwane’s stagewear and when the nu-folk movement was still definably a ‘thing’, the quality it prized above all others was authenticity. For a small congregation of privileged west London teens and twenty-somethings on their starter beards, in love with the idea of being minstrels and troubadours, it was an understandable fixation. But Laura Marling, the most precocious and preternatural of the lot of them, was always a little bit different: her main concern was honesty, which isn’t quite the same thing.Those one-time contemporaries have since gone their separate ways.

Based on rating 4.5

Artistic intent is notoriously difficult to pin down, yet the first line of Laura Marling’s new record is a clear statement. Signifying a continuing personal battle, Marling – slightly hesitantly and tremulously – sings “You should be gone beast / be gone from me,” over lazily thumbed chords. It’s somehow both self-flagellating and defiant, echoing the sentiments of her previous album, the troubled A Creature I Don’t Know.

Based on rating 8.5/10

In an age when single song downloads have become the norm and attention spans seem to be shrinking, concept albums—which generally tell a single overarching story and, therefore, work best when presented as a whole—have become increasingly less feasible. Laura Marling’s latest album, Once I Was An Eagle, the fourth in her young but impressive career, bucks the trend and succeeds wildly because of it. It’s an ambitious album—and not just because it requires listeners to set aside more than an hour of their time to fully appreciate its individual pieces.

Based on rating 8.5/10

The song that, for all intents and purposes, proved to be Laura Marling’s breakthrough provides an interesting instrument with which to gauge her relentless progression over the course of her short career to date. ‘New Romantic’ is wonderfully written; honest, witty, somehow both charming and heartbreaking, and yet it seems, by way of comparison to what’s come since, almost juvenile. The failed-relationship basics of the lyrics stand out; Marling doesn’t write songs with turns of phrase like ‘pretty fit’ any more.

Based on rating 85%%

What were you doing when you were 23? While you were sleeping, Silver Lake–via-UK singer-songwriter Laura Marling is releasing her fourth studio album, which is the best work of her career. The 16-song Once I Was An Eagle—which had its vocals and acoustic guitar recorded live in one take—is a not only a work of literary storytelling but consists of timeless art and wisdom from a budding songwriter who is still learning and exploring what it means to be human and what it means to be defiant in the face of love as she grows older. Although the songs carry recurring tropes of eagles, devils and the sea, as well as her signature intricate guitar picking, the most haunting aspect is—considering this accomplishment—realizing the potential that is yet to come.

Based on rating 8.1/10

Laura Marling has spent the first few years of her career in a state of perpetual arrival. Alas I Cannot Swim-- her 2008 debut, made when she was 18-- was a bright, brooding collection that set her up as the darling of the latest British folk revival and saw her nominated for the Mercury Music Prize; a feat she repeated with 2010's more polished I Speak Because I Can. On 2011's sprawling A Creature I Don’t Know, she further established herself as an ambitious artist with a widening, sharpening vision.

Based on rating 4/5

As Laura Marling begins her fourth album Once I Was An Eagle, she sounds wounded and vulnerable, singing “You said ‘Be gone, baby,’” in the gentle opening song “Take the Night Off. ” But Marling isn’t so much wallowing in self-pity as taking stock of what went wrong. She’s mired in a heart-broken love hangover that opens up over the next three tracks, and as this interconnected song-cycle progresses, a backing of bongos and sitar create a psychedelic, dream-like state for Marling to muse as her scar tissue stitches together.

Based on rating 80%%

Laura MarlingOnce I Was An Eagle[Virgin; 2013]By Ray Finlayson; June 3, 2013Purchase at: Insound (Vinyl) | Amazon (MP3 & CD) | iTunes | MOGThe first real taste of Laura Marling’s new album came via a short film called When Brave Bird Saved, which allowed the listener to take in the first four songs of Once I Was Eagle. Those four songs – “Take The Night Off,” “I Was And Eagle,” “You Know,” and “Breathe” - are one, fusing together to create a medley. The transitions are as seamless as the dance moves in the film, and while some might say Marling’s guitar and voice are a touch too blocky and dry to be put to choreography (not in the same way as the likes of Max Richter or Sigur Rós), the focus is instead on the emotional process Marling character is going through.

Based on rating 4/5

Certainly, by the last song, Saved These Words, she knows one thing for sure. All of those relationships, some of them semi-public (musicians Charlie Fink and Marcus Mumford)? "You weren't my curse," she says of one of them (or all of them) or, indeed, as a warning to the next one: "He was my next verse." .

Based on rating 8/10

It's hard to think of an artist that has shown as much musical growth in as short a time, but on her fourth album in five years, Laura Marling has proved that she is a force to be reckoned with. For the first time, Marling eschewed collaborating with a band, in favour of an intimate working relationship with long-time studio partner Ethan Johns (Ryan Adams, Kings of Leon). His handiwork is heard right off the bat, having trimmed down opener "Take the Night Off" from its once 20 minutes.

Based on rating 4/5

Occasionally, you're reminded that, for all the snarling confidence on display, Marling is still an artist in the process of finding her own voice. Shortly after finishing the album, she moved to Los Angeles, perhaps to be reunited with her accent, which, on the evidence presented here, seems to have emigrated to America some time before she did. At one point, this gets so out of hand that she pronounces the word "verse" as "voice", which would be fair enough had she grown up in Flatbush, Brooklyn, but feels a bit affected given that she grew up in a Hampshire village called Eversley.

Based on rating 7.5/10

As a songwriter, Laura Marling has always gone toe-to-toe with her womanhood and its role in her relationships. Her latest effort, Once I Was An Eagle, sees her address this from two distinct aspects—first as a woman fractured and broken, later, with a confidence and conviction rebuilt..

Based on rating 3.7/5

Review Summary: "And damn all those hippies, who stomp empty-footed upon all that's good, all that's pure in the world" English folk musician Laura Marling’s latest release is a living and breathing labyrinth. it’s acutely self-aware of how its ends meet in all the clever ways, like its signature melody that both begins and ends matters, its familiarity veiled behind a simple mirror image. The record begins with bursts of blissful ascension, the notes within lingering in the air long after they’ve been played-- so that when an eerily familiar succession of notes cracks through the surface in the final song’s cessation, it’s both comforting and meaningful.

Based on rating B

Laura Marling’s ivory vocals may be as lovely as the English countryside, but don?t call her demure. The 23-year-old London native has been writing and recording since she was 16 while notoriously maintaining her distance from the stage. The young artist is notably shy while performing and choosy with her interviews. But her selectivity only seems like a testament to her humility.

Based on rating 7/10

Once I Was an Eagle, the fourth long-player from Laura Marling, finds the spectral folk singer relocating to Los Angeles, abandoning her backing band, and delivering a cumbersome yet remarkably confident 16-track, 63-minute collection of alternately intimate and grandiose pre-, present, and post-relationship songs that more or less obliterate her reputation as a stage fright-ridden, pale English flower. The first four tracks, which begin with the languid "Take the Night Off" ("You should be gone beast/be gone from me/be gone from my mind at least/let a little lady be") essentially form a suite, seamlessly flowing in and out of each other like an impromptu, post-breakfast, tobacco smoke-filled rehearsal that just happened to occur amidst a sea of expensive microphones. Marling's reinvention as a Californian will do little to quell all of the Joni Mitchell comparisons which, let's face it, are pretty apt, but songs like "Breathe," "Master Hunter," "Pray for Me," and the quasi-mystical title cut introduce Indian ragas, open tunings, and cathartic, tabla-fueled breakdowns into the mix, suggesting a steady diet of Led Zeppelin III, Pink Floyd's Meddle, and Pentangle as well, which adds to the album's dusty, Laurel Canyon patina.

Based on rating 7/10

In anything you write about Laura Marling, there’s two things you should try to avoid mentioning, that are actually really hard to ignore. First of all, that she came from the same crowd as Mystery Jets, Noah & The Whale, The Vaccines and Mumford & Sons. Not that Marling is so different from these bands – they obviously share a bunch of influences, and some of them have eclipsed Marling in terms of sales and chart significance.

Based on rating 3/5

"It ain't me, babe," sings Laura Marling in "Master Hunter," echoing Dylan for her own back-the-fuck-off-my-love song. Since her days singing folk pop with the Mumford & Sons clan, she's followed her own muse to more-interesting places. Her fourth LP begins with seven songs linked by drones, lyric shards and a suicide-haunted relationship. The set goes on to explore loneliness in brighter shades, with percussion, strings and organ-coloring acoustic guitar.

Opinion: Fantastic

byJERRICK ADAMS It wasn’t until the fourth or fifth spin of Laura Marling’s fourth LP, Once I Was an Eagle, that I began to hit upon what it is that makes this a great record. I knew from the first that it was overwhelmingly strange, and that this strangeness was the key to understanding the record. But how do you describe strangeness, such a relative and therefore slippery concept to begin with? Of course, some of that strangeness comes from Marling’s voice.

Opinion: Fantastic

“Take the night off and be bad for me,” croons Laura Marling on the opening track of Once I Was An Eagle, starting off what can only be described as an achingly small album of epic proportions. Following the course of the emotional toil after a bad relationship, Marling, the British folk-rock darling, puts a brittle, urgent edge on the classic idea of the break-up album. Marling reportedly recorded the whole album in 10 days, taking only one day to record all of her vocals and guitar parts.

Opinion: Fantastic

Sometimes it feels like music is more interested in bells and whistles than it is the humble appeal of a melody. If you’re not whirling silken ribbons whilst simultaneously reverse coding the tandura through the innards of a vintage synthesiser found in the Oxfam near Gary Numan’s old house, you’re quite frankly not trying hard enough. And if, lord forbid, you’re happy with a humble guitar - that produces a thousand facets of different enchanting shades, a softly husky vocal that bites and magnifies to Goliath, before metamorphosing to the shaking David in one pause - prepare to be reduced to one painfully inadequate descriptor.

Opinion: Excellent

It’s hard to say why Laura Marling opens her new album with a suite of four songs that, taken together, are nearly impenetrable. Lumbering and lugubrious, they bleed into one another with rarely a spike in her voice or shift in tempo or even key. It’s a deceptive start to “Once I Was an Eagle,” the fourth release from this sage, 23-year-old English singer-songwriter.

Opinion: Great

Laura Marling always had an epic in her. Even from her earliest teenage recordings, such as her 2008 debut, "Alas, I Cannot Swim," her songs had the stuff of myths — suicide, revenge, impossible love. With "Once I Was an Eagle," she's finally made a record that matches the magnitude of her vision, and puts her well ahead of almost any twentysomething singer-songwriter peer working today.

'Once I Was an Eagle'

is available now