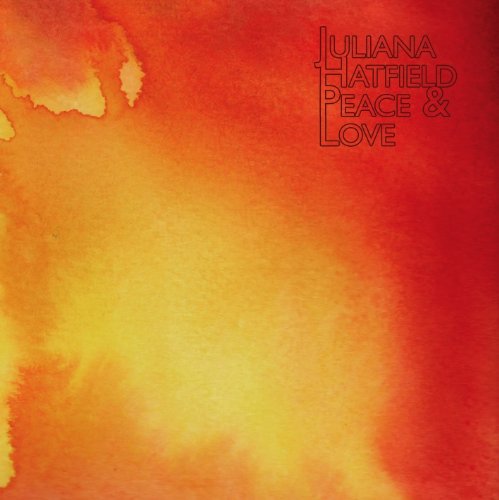

Juliana Hatfield

Peace And Love

Release Date: Feb 16, 2010

Genre(s): Rock, Alternative, Singer-Songwriter

Record label: Ye Olde

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Album Review: Peace And Love by Juliana Hatfield

Acceptable, Based on 4 Critics

Based on rating 8/10

Starkly contrasting with the assured studiocraft of How to Walk Away, Peace & Love presents Juliana Hatfield unadorned. Largely acoustic and spare -- the piano of “Why Can’t We Love Each Other” and insistent rhythms of “Let’s Go Home” standing out all the more in this context -- Peace & Love has the feeling of a confessional, a suspicion reinforced by the existence of songs like “Evan” that feel like a letter to a longtime friend. Autobiography has always been an element of Hatfield’s work, something she made plain in her memoir and accompanying blog, but viewing this album as a strict journal does a disservice to Juliana’s writing, whether it’s her gift for a sly turn of lyrical phrase or how her melodies rise and fall with a natural grace.

Based on rating 7.1/10

Modest atmosphere, fearless honesty The circularity of the modern rock ride is unnerving sometimes. The Blake Babies’ cult momentum brought Juliana Hatfield to the doorstep of Atlantic Records nearly 20 years ago, and you wonder if she would’ve flinched knowing that her 11th album two decades later would be self-recorded in a Cambridge bedroom. If forced modesty is the hallmark of the current business model, at least Hatfield has the grace to pull it off without bitterness or recrimination.

Based on rating 3.9/10

By now, Juliana Hatfield's business accomplishments have far outstripped her musical ones. In the early 1990s, she turned her cult notoriety with Blake Babies into "120 Minutes" buzz, and she harnessed the momentum from her 1993 decent-seller Become What You Are into something resembling a career. She's still going strong at a time when most of her alt-peers have long ago faded into obscurity or nostalgia tours.

Based on rating 2/10

For those of us who came of age in the era of Slap Bracelets, Crystal Pepsi, and Pogs, the ‘90s are a bit of a sacred cow. One of the current indie generation’s defining aspects is its penchant for nostalgia—and it serves as a kind of revisionist history that in retrospect we have painted the alternative era as this golden age of MTV video blocks and Dickies flannel jackets, while carefully omitting home truths about the period’s less pleasant memories (the Oklahoma City bombing, the OJ Simpson murders). In our age of Auto-Tuned pop starlets, bling, and MTV forgetting music altogether, the nineties provide a comfortable safe haven to retreat towards, one of those rare spaces of years where the popular music on the radio was also the artistically important music.