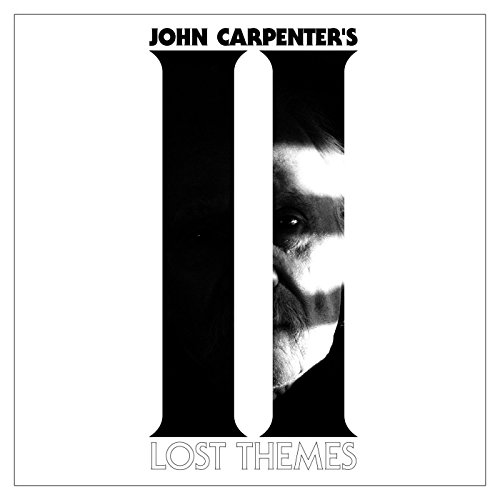

John Carpenter

Lost Themes II

Release Date: Apr 15, 2016

Genre(s): Electronic

Record label: Sacred Bones

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy Lost Themes II from Amazon

Album Review: Lost Themes II by John Carpenter

Fairly Good, Based on 13 Critics

Based on rating 8/10

After a lengthy period of silence, the 2010s saw a burst of activity from John Carpenter: he released Lost Themes II in 2016, just a year after his first album of non-soundtrack music arrived. The release of pent-up creativity within Lost Themes' wonderfully over the top songs was almost palpable, but its sequel is more streamlined, more confident, and more like Carpenter's actual soundtrack work. This time, Carpenter, son Cody, and godson Daniel Davies recorded these songs in the same studio instead of collaborating long-distance, giving Lost Themes II a cohesion that allows them to explore more moods and settings.

Based on rating 4/5

There's always a strong sense of trepidation when it comes to approaching any sequel; difficult to supress the scepticism that it's not the usual indolent offering of dusted-down scraps from the cutting room floor, dredged up in the name of a quick and easy buck. Not so with Lost Themes II, the companion and in every way equal counterpart to horror legend John Carpenter's surprise (and superb) release of last year. The unashamedly 80s aesthetic – which hallmarked the first Lost Themes – is pleasingly and emphatically recurrent on the second.

Based on rating B

It’s funny how John Carpenter couldn’t be further removed from his own creations. For years, he carved out hypermasculine anti-heroes, mostly in the visage of Kurt Russell, who stormed through his best pictures with questionable moral codes yet steely determination. The Master of Horror, however, would be quite complacent escaping reality and focusing, instead, on an NBA game while he nurses a cold beer or a warm joint.

Based on rating 3.5

As anyone with a even passing interest in cinema will know, John Carpenter made some of the most highly regarded, and enjoyed movies of the late ’70s and early ’80s. His run of classics starts with Assault On Precinct 13 and Halloween and then runs into the likes of The Fog, The Thing, Big Trouble In Little China and Escape From New York. Not only did he write many of these movies, he wrote the scores as well.

Based on rating 7/10

On Lost Themes II, as on last years' Lost Themes, famed filmmaker and synth-horror musician John Carpenter brings a stable of tracks ripped right out of the '80s. The album is full of deep synth leads and flange filters, each feeling like it could be extended and riffed on to create the central motif for a film. The themes are dark and moody here, so while horror is an obvious influence, the themes could fit well in drama, as they channel heaps of emotion alongside the requisite tension.

Based on rating 3/5

Lutenist and minimalist composer Jozef Van Wissem has released close to a solo album a year since the turn of the century. His latest continues to demonstrate both the versatility of his instrument and its owner, while featuring guest vocals from frequent collaborator Zola Jesus. While the lute is often characterised as being a medieval or Baroque instrument, Van Wissem has no qualms about testing its limitations.

Based on rating 6/10

What would contemporary music, particularly electronic music, sound like if John Carpenter had resigned himself to just being a director? The composer's soundtrack work is as iconic - if not more so - than the films they are created for. From the chilling piano melody and atmospheric strings of the Halloween soundtrack (particularly on 'Laurie Knows') to the thick, industrial bass synth of Assault On Precinct 13's main title, Carpenter has created music that is as evocative, as thrilling, as terrifying as the films themselves. Of course, it's impossible to separate a film's score from the images it accompanies.

Based on rating 6/10

John Carpenter’s contribution to the music of cinema is staggering. It’s hard to think of any soundtrack or score, excepting perhaps the Exorcist’s use of ‘Tubular Bells’, that defines the primal chill of good horror as much as his minimal work on Halloween, where a simple four-note synth line ('da duh-duh da duh-duh dah dah') is as relentless and insistent as the unstoppable killer it accompanies. His analog synthscapes are simultaneously cold and warm.

Based on rating 6/10

Now that budgets for films that reside in John Carpenter's wheelhouse have become all but extinct, the auteur behind iconic films like Halloween and Escape from New York has taken his side hustle as a film composer—and popularizer of the analog synth—into the spotlight. He's even assembled a band: Daniel Davies and his son, Cody Carpenter, record and (as of very recently) perform live with Mr. Carpenter.

Based on rating 3/5

Given that director-composer John Carpenter’s electronic scores were so integral to his classic 70s and 80s horror movies, from The Fog to Halloween, it’s a wonder that he waited so long to release an album. However, following 2015’s Lost Themes, this is his second such offering in 14 months. Made (again) with his son and godson, it pairs sinister synthesisers with chugging, almost prog-rock guitars, bass and drums.

Based on rating 5.6/10

The only direct sequel John Carpenter directed in his career was Escape from LA, and the critical reaction to his follow up to anti-hero Snake Plissken's New York adventures in the post apocalyptic millennial hellscape of urban America was a mixed bag. In 1996 for the New York Times Stephen Holden wrote that the movie barely kept afloat amidst its conceit of "hopelessly choppy adventure spoof." In his over forty-year film career Carpenter has cultivated a reputation that rests on a take-it-or-leave-it attitude to camp glory. Either it touches your or it doesn't.

Based on rating 2.5/5

“I DON’T KNOW WHAT THE HELL IS IN THERE” I’m sitting on my couch, and the thing is sitting in my lap. I look at it, turn it over in my hands, consider its promises.. “Hear your horror.”.

Opinion: Fairly Good

Recently, after a regrettable trip to see the Razzie-baiting Batman vs Superman, my companion turned to me and said something I never expected to hear [SPOILER ALERT]: "If I see Neil DeGrass Tyson appear as himself in one more film," he told me, "I am going to join B.o.B's flat earth conspiracy cult out of pure spite". Despite my mostly platonic affections for the well-moustachioed physicist, I could see that my friend had a point. Every respected authority can only make so much capital out of the goodwill of their fans and acolytes before the same qualities that attracted fame and fan fervour in the first place become causes for derision.

'Lost Themes II'

is available now