EMA

Exile in the Outer Ring

Release Date: Aug 25, 2017

Genre(s): Pop/Rock, Alternative/Indie Rock

Record label: City Slang

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy Exile in the Outer Ring from Amazon

Album Review: Exile in the Outer Ring by EMA

Excellent, Based on 10 Critics

Based on rating 9/10

I'll admit: sometimes, when I sit down to write a review, I think about what the other writers (mostly male) might do. In this case, I projected, they’re gonna size up Erika Anderson, measure the size of perceived stab wounds, tease out sources of trauma, and come away with prophetic verses like 'this is the voice of America in 2017' or 'EMA is the most radical chick in the game right now'. They will blow up her disconnected past, trace her present pilgrimage into the outskirts of Portland, and declare the future altered.

Based on rating 8/10

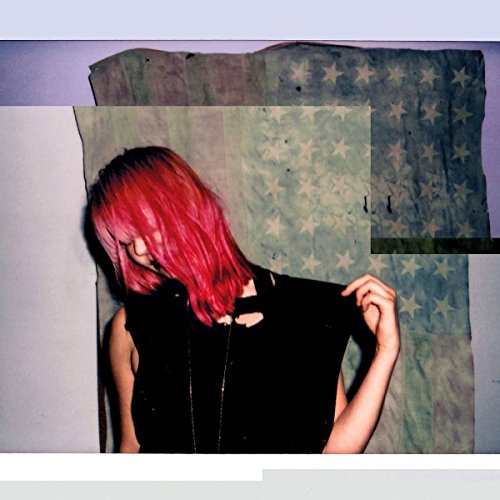

Erika M. Anderson grew up in the outer ring, the suburbs and back roads around major cities across the United States. Between reurbanization, globalization and the Internet's impact on industry, these neighborhoods are hollowed-out and in decline. The hopes of these communities became as dried up and faded as the American flag behind EMA on the cover of Exile In The Outer Ring.

Based on rating 8/10

"I Wanna Destroy" is contained anger. Here, EMA 's words reveal a craving to break with a frustrating state of insignificance and irrelevance. Her music does not have a climactic explosion, instead, it's a progression of intensity, steady and restless .

Based on rating 8/10

Erika M. Anderson can always be counted on to be painfully honest and direct. She's opened one of her most well-known tunes with the line, "Fuck California / You made me boring," and she slathers her material with noise-drenched, visceral soundscapes and searing lyricism. The emotional, heart-on-sleeve approach suits her well, and it's one that she uses to great effect on new album Exile in the Outer Ring. This raw, confessional style is especially perfect given Anderson's attempt to convey the rage and resentment experienced by middle ….

Based on rating 4

EMA, aka Erika Anderson, has pretty much always failed to meet expectations. She’s far more interesting than that. From her work with noise-folk trio Gowns, through to her critically acclaimed solo debut Past Life Martyred Saints, and its follow up The Future’s Void, there’s a distinct sense that she has made music to please herself, rather than record labels, the media or anyone else.

Based on rating 4/5

South Dakota’s Erika M Anderson continues to mine the fraught terrain between the topical and personal on her third album. If that tension galvanised the grunge-drone snapshots of young American anxieties on 2011’s Past Life Martyred Saints, it brought fresh urgency to 2014’s The Future’s Void, where EMA decried our oversharing age. For Exile, she shifts her focus from privacy to poverty, adopting the voices of those exiled from the US’ centres. EMA’s powers of empathetic evocation prove potent; she consistently builds in goth-industrial muscle and range upon her art-punk stylings.

Based on rating 7.5/10

There's a simple elegance to Erika M. Anderson's music, produced under the name EMA. Sometimes her sound fills out with reverb and distortion, giving it a more complicated feel, but at her best she's a crafter of impressively haunting pop songs that serve rather than distort the message. Make no mistake, this is a political record, a snapshot of a society lost and angry.

Based on rating 7/10

Aside from being an amalgam of Erika Michelle Anderson’s initials, the recording moniker EMA sounds like it could be an illicit substance. You could imagine the name denoting something that is best taken in the dark when you want to concentrate all your energy on another person. Through Exile in the Outer Ring, EMA creates a jagged, broken mirror world where communication is garbled by literal debris and by invocations of higher powers, like Jesus and the Devil.

Based on rating 3.5/5

Loud, unrepentant and able to reshape the space around her as a temporary autonomous zone, Erika M. Anderson inhabits the songs on her third album like a denim-clad dirtbag blasting Rush in the 7-Eleven parking lot by dawn's early light. Her music is constructed around cresting and collapsing waves of static, feedback and groaning synthesizers. The simple melodies promise resolutions that never arrive.

Opinion: Excellent

Late last year, during the interregnum between Donald Trump’s election and his accession to the White House, my partner and I travelled throughout the United States. As we drove between the liberal, artsy oases of the West Texas desert towards Santa Fe, New Mexico (another liberal, artsy oasis), we rode through a long stretch of oil country. The highways were terrifying in their quotidian bleakness: billboards on either sides advertised the importance of keeping Naltrexone in the house in case a loved one overdosed on opioids, or the services of personal-injury lawyers if you were involved in a crash with one of the oil trucks that domineer the highways here.

'Exile in the Outer Ring'

is available now