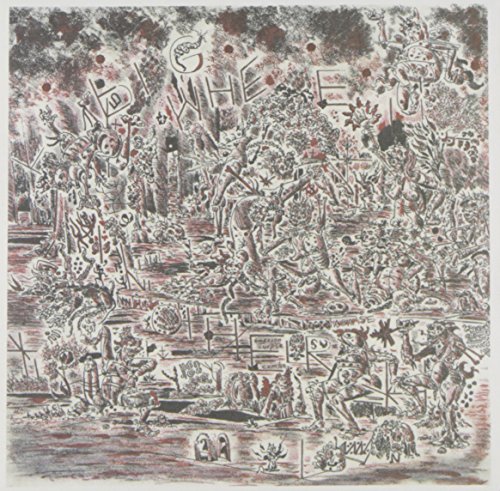

Cass McCombs

Big Wheel and Others

Release Date: Oct 15, 2013

Genre(s): Pop/Rock, Alternative/Indie Rock, Indie Rock, Indie Pop

Record label: Domino

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy Big Wheel and Others from Amazon

Album Review: Big Wheel and Others by Cass McCombs

Very Good, Based on 19 Critics

Based on rating 9.2/10

I’m going to tell a story about a song, because I think it matters. Ten years ago, Cass McCombs recorded “Bobby, King of Boys Town,” a track that’s as good as any other. The lyrics are nothing more than a reel of boy’s room boasts and taunts (“Ain’t a man alive I fear,” “Where’d you learn to smoke?/ Cause you’re doin’ it all wrong”), yet from those spare strokes the image of a spit-cool foster kid emerges, a boy whose swagger masks everything you can imagine.

Based on rating 85%%

Cass McCombs’ weaving narratives flow through the nomadic troubadour’s musical apparatuses with the same aplomb and abandon they use to slink the gaps between the vertebrae of the listener. A double album announced two months prior to its release—coming off the twin triumphs of 2011’s Wit’s End and Humor Risk, no less—Big Wheel and Others represents McCombs’ most transient yet memorable volume of song-carved verse yet. It’s a (relatively) sanguine, folked affair, unafraid to grin sidelong at its own mortality.

Based on rating 8/10

California troubadour Cass McCombs might just be the most famous hobo you could name. Think of all the reasons why a stable roof over your head is advantageous and he'll show you seven-and-a-half albums why a shelter-free existence works for him. In 2011 alone, he released two of the year's finest records, Wit's End and Humor Risk, demonstrating he can have prolific surges.

Based on rating 4/5

For a guy who told NOW last year that he hopes there won't be records in the future, Cass McCombs records a lot of music. His "seventh and a half" album is nearly an hour and a half long and spans two discs, its 19 songs interspersed with audio clips from a 1970 documentary called Sean (in which a four-year-old talks about dogs, cops and drugs). It even opens with a song about heavy machinery, masculinity and driving long distances alone (Big Wheel).

Based on rating 8/10

Cass McCombs has always been restlessly prolific, and his contemplative lyricism and traditional chord patterns have always given the impression of a man who writes a dozen songs a day. But Big Wheel and Other Things is undoubtedly McCombs’ greatest outpouring of unrestrained creativity: a 22-track, 90-minute opus of his loose, soulful, macabre jams. And by using the marathon running time to distil all of the what we’ve previously heard from McCombs into a collection of songs as good as he’s ever crafted, the record stands as his most immersive and stirring to date.

Based on rating 7.9/10

Few things are as quintessentially American as the mythos surrounding the West. Manifest destiny, the romance of wide open plains and broken landscapes, get rich quick schemes, and old-fashioned wandering. Cass McCombs’ seventh full-length album, Big Wheel and Others, takes root in this fertile soil of Americana, crafting a sprawling cosmology out of its characters from the past two centuries.

Based on rating 7.5/10

Cass McCombs returns with a double album, drifting around the genre map and proving his prolificacy can't depend on any particular narrative, any overarching marketable story beyond, perhaps, the utilitarian version/vision of songcraft. With that in mind, let's just slap him with the "enigmatic" tag and discuss a few of the more perfect constructions presented here. .

Based on rating 3.5/5

Alright; Cass McCombs’ career to date has basically been a long series of feints. Whether it’s outlining his own origin myth, kicking off his first album proper by dying in a hospital, or weighing down a nigh perfect album with maybe the most irritating song anyone’s written this decade, he’s done as much as he can in his power to make sure he’s out of reach, let alone someone your dad might come across in a copy of MOJO. He’s off every map you care to mention, ostensibly governed by the lyric sheet for “The Seventh Seal” more than anything else.

Based on rating 6/10

Cass McCombs is a private, relatively unknowable musician. You have his music—which itself is evasive in its uses of deep melancholy streaked with humor, in the ways in which it shifts shape from album to album—but it doesn’t tell you much about him. It’s a curious stance in these days of open-source lifestyle, but McCombs stands as an interesting lesson: albums won’t necessarily tell us about their creators, and they don’t need to if they wish to be revealing.

Based on rating 3/5

Beyond the fact that it contains 19 songs (plus three interludes featuring an inane but quite sweet chat with a small boy), there’s nothing stylistically ‘double album’ about this double album. No sprawling space odyssey theme, no acoustic flipside; just lots and lots of Cass McCombs songs. Which, in theory, is no bad thing – and indeed, the slide guitar-drenched ‘Angel Blood’ is McCombs at his hypnotic, country-downbeat best.

Based on rating 6/10

Following a remarkably prolific 2011, which saw the release of not one but two strong-in-their-own-right full-length records (Wit's End and Humor Risk) from indie troubadour Cass McCombs, things got relatively quiet for the ever-evolving songwriter. His complexly poetic lyricism and subtly textured musicianship were in prime form on both albums, reaching into different places of darkness and humor. Two years later, Big Wheel and Others arrived; a sprawling 22-track collection that clocks in at almost 90 minutes and shows McCombs trying on different hats in his own established way of slowly unraveling his patient, aching compositions.

Based on rating C+

Be patient with Cass McCombs. Not because his music is demanding or dense in any quantitative way – his seventh album, Big Wheel and Others, is his most adventurous since 2007’s Dropping the Writ, but that’s merely because it’s peppered with strings and squalling sax and pattering drums. No, you have to be a little patient with McCombs, 35, because he records material as eloquent as it is glacial, and some of his latter-period songs have a haunting brevity comparable to that of Raymond Carver’s short stories – you can’t intake many at a time or they won’t sink in.

Based on rating 2/5

‘Big Wheel And Others’ is the seventh full-length album from the nomadic Cass McCombs, a double-album comprising 22 tracks and clocking in at a combined running time of 85 minutes. The cult singer songwriter skips effortlessly through folk, country, blues, ballads and jazz with his trademark wit. Despite such stylistic diversity this is a collection of songs firmly entrenched in melancholy which is why ‘Satan Is My Toy’ is such a jolt to the system, pairing an intoxicating funk groove that comes on like a streamlined Primal Scream jamming with Kasabian.

Opinion: Fantastic

Cass McCombs Big Wheel and Others (Domino) Gentle outlaw Cass McCombs luxuriates in sunlit California landscapes, weaving offbeat tales of carousing and yearning on Big Wheel and Others. Running a languid 85 minutes, his seventh studio album – a double – sifts through the dust of the Old West anchored by Dan Iead's whining steel guitar ("Angel Blood," "Everything Has to Be Just-So"), and grounded in the earthy percussion of Parker Kindred. On the title cut, McCombs' acoustic guitar uptempos through Left Coast truck-stop restlessness, pausing just long enough to reference the hymn "Peace in the Valley." As ever, the hero here is the singer's golden voice, equal parts Dire Straits' Mark Knopfler and the Shins' James Mercer.

Opinion: Excellent

Cass McCombs could be the missing link between Howe Gelb and Bill Callahan. It seems that way while foraging through the double-disc Big Wheel and Others, the second part of the title accounting for 21 other tracks. His wizened whisper (sounding like it gained its knowledge through the consumption of too many glasses the night before) recalls Gelb. The occasional high lonesome guitar that yowls in the background puts McCombs on the same highway that the Giant Sand man might have traversed sometime over the past two decades.

Opinion: Excellent

Affliction is a luxury, just another thing to flaunt, on “Suffering From Success,” the seventh album by DJ Khaled. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, though it’s a minor deviation from the norm. DJ Khaled, 37, has been one of hip-hop’s most dogged purveyors of exultation, which is saying something; his previous albums came with titles like “We the Best,” “Victory” and “We the Best Forever.” Even here, working within a cloud of notional anguish, it’s clear that he courts your envy, not your pity.

Opinion: Very Good

Unless you are listening to one of his seven albums, perhaps a little hypnotised by his gifts and the one setting in which everything about Cass McCombs seems to make sense, this artist can seem a perplexing figure. There are few like him; his distaste for all things 'industry' and 'promotion' is well documented, while he categorically refuses to put any of his songs in any sort of context. On stage he sings his songs and offers no engagement whatsoever, while still being an electrifying performer.

Opinion: Very Good

opinion byBENJI TAYLOR There’s always been more than a touch of the medieval troubadour about Cass McCombs: preoccupied with the notion of god, of no fixed abode, and with a dislike of the press and the music industry in general, it often felt as if he’d been born in the wrong place and in the wrong time. And that was what made his music so absorbing and compelling – these were tunes and tales told from the vantage point of a mysterious drifter - from the dark brooding beauty of 2011’s Wit’s End to the rambling poetic brilliance of 2009’s Catacombs. The sense of otherworldliness that accompanied McCombs lent an edge of timelessness to his music that made his songs and the ideas they explored almost impossible to shake off.

Opinion: Fairly Good

If you think about it in retrospect, the signs of fatigue were there at the end of 2011. By that point, nomadic singer-songwriter Cass McCombs had released two full length albums, WIT’S END and Humor Risk. While the former was a record up there with McCombs’ best work, Catacombs, and further testament to his rare talent for combining a keen sense of humour with his Dylanesque writing style, the latter felt like a step too far: moody, muddled and really quite a bit of a downer.

'Big Wheel and Others'

is available now