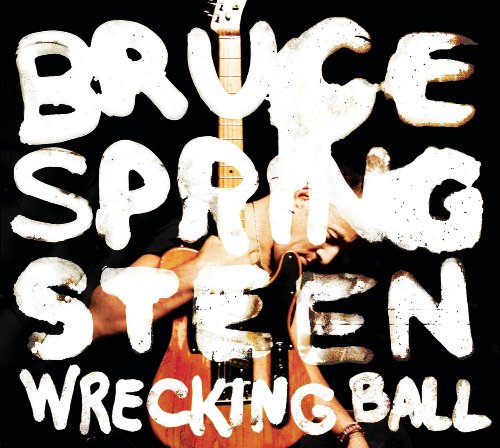

Bruce Springsteen

Wrecking Ball

Release Date: Mar 6, 2012

Genre(s): Pop/Rock, Contemporary Pop/Rock, Rock & Roll

Record label: Columbia

Music Critic Score

How the Music Critic Score works

Buy Wrecking Ball from Amazon

Album Review: Wrecking Ball by Bruce Springsteen

Very Good, Based on 24 Critics

Based on rating 5/5

Wrecking Ball is the most despairing, confrontational and musically turbulent album Bruce Springsteen has ever made. He is angry and accusing in these songs, to the point of exhaustion, with grave reason. The America here is a scorched earth: razed by profiteers, and suffering a shameful erosion in truly democratic values and national charity. The surrender running through the chain-gang march and Springsteen's muddy-river growl in "Shackled and Drawn"; the double meaning loaded into the ballad "This Depression"; the reproach driving "We Take Care of Our Own," a song so obviously about abandoned ideals and mutual blame that no candidate would dare touch it: This is darkness gone way past the edge of town, to the heart of the republic.

Based on rating 9/10

Bruce Springsteen’s longtime collaborator Jon Landau has described Wrecking Ball as Bruce Springsteen’s “angriest album yet”. And while that description may be apt for the first half of The Boss’s 17th studio album, it later becomes clear that it may be his most spiritual album. It has been a long time since Bruce Springsteen has taken us from A to B so efficiently, and although the purpose and clarity may be slightly muddled in the anger on the earlier songs, there is plenty to love here; namely, the richest, most dynamic album to the legend’s name in decades.

Based on rating 9/10

Not so long ago, it looked like Bruce Springsteen was thoroughly Bruuuced-out and would never make rock records again. Back in 1995, three years after firing the E Street Band and, for some damned reason, touring without them behind a pair of ill-received albums (the simultaneously released Human Touch and Lucky Town), Springsteen surfaced with a mustache and ponytail, released a somber folk album (The Ghost of Tom Joad), and went on a solo-acoustic theater tour. Bruce looked thickish, sang only in drawls and whispers, and wouldn’t release another album for seven more years, and as each of those years passed, Springsteen Nation grew increasingly worried that their hero would never again sing “Badlands” in a packed arena, let alone a stadium, standing in front of the E Street Band.

Based on rating 8/10

On the heels of last fall's Occupy Wall Street protests arrives Bruce Springsteen's Wrecking Ball, his most vibrant studio album of original material since 1984's Born in the U. S. A.

Based on rating 4/5

From the ‘Born To Run’ glockenspiel chimes to its easily-misinterpreted-as-patriotic sentiment, the lead-off track from Springsteen’s 17th album – a song called ‘We Take Care Of Our Own’ – suggests familiar ground lies ahead. Furthermore, another of its songs – the epic ‘Land Of Hope And Dreams’ – was first played live in ’99, and features imagery of “[i]thunder rollin’ down the track[/i]”. So far, so Bruce.But then, if ever America needed a fired-up Boss doing what he does best – in his words, “measuring the distance between the American Dream and American reality” – it’s in 2012.

Based on rating 4/5

Over the last 30 years, Bruce Springsteen's career occasionally seems to have hinged not on changing tastes or fashions, but on world events. The album that propelled him to global superstardom, 1984's Born in the USA, was born out of the early-80s recession and became entangled in Ronald Reagan's re-election campaign, albeit unwittingly. The "lost decade" that began with 1992's Human Touch was brought to an end by 2002's The Rising, an album spurred by 9/11.

Based on rating B

When Bruce Springsteen announced that his new album, Wrecking Ball, would contain somewhat out-of-character sonic touches such as loops, electronic percussion, and (gasp!) hip-hop, fans and critics alike had good reason to be skeptical. The Boss’ musical experiments have never been as head-scratchingly risky or weird as, say, Neil Young’s, but they’ve often yielded equally mixed results in the past. Whereas the haunting acoustics and bleak outlook of Nebraska were a welcome change, the similarly minded The Ghost of Tom Joad resulted in a pretty boring record, despite a handful of choice cuts.

Based on rating B

The recession has been rough on everyone — except maybe Bruce Springsteen, who’s emerged with some good material for his new album. He says Wrecking Ball was inspired by Occupy Wall Street, and even though some of these songs were written before anyone pointed a bullhorn at the banks, he’s smart to make that declaration. Whenever America’s falling on hard times, his music simply sounds better, his lyrics taking on near-biblical significance.

Based on rating 3.5/5

What does America mean to you? For our international readers, answering that question may be a purely intellectual exercise, but for those of you out there who, like me, were born and raised right here in the U.S. of A., forming a response probably isn’t so simple. We of generation 9/11 have a complicated relationship to patriotism. We were ushered into adulthood by the terrified exaltation that accompanied our vast and fragmented nation setting aside those things that divided it to rally around the victims of an unthinkable atrocity.

Based on rating 7/10

One of the upsides to the world going to shit is that it tends to bring out the best in Bruce Springsteen, an artist who – notwithstanding the magnificent The Ghost of Tom Joad - was practically mothballed in the Nineties, only returning to active service post-9/11. Surprisingly, maybe, Wrecking Ball is the first of the six albums he’s put out since 2002 to be overtly, unambiguously politicised: despite its undeniable resonance, The Rising wasn’t substantially a record about 9/11, and though the protest folk covers of the super We Shall Overcome were clearly tilted at the Bush administration, the project was indubitably about Springsteen’s love of the music first and foremost (it seems unlikely ‘Froggie Went A-Courtin’ rattled too many neocon cages). Wrecking Ball is pretty unambiguous, though.

Based on rating 7.0/10

The Boss has always had an uneasy relationship with fame—not so much the celebrity aspect, but the wealth. Singing about the American working class made him wealthy, which in turn distanced him from his own subject. On every album since 1984’s legendary Born in the USA, Springsteen has worked visibly hard to maintain those ties to his roots, and a few misfires aside, he’s managed to make some meaningful music through sheer determination and earnestness.

Based on rating 6/10

Heavy lies the crown on Bruce Springsteen's head. Alone among his generation -- or any subsequent generation, actually -- he has shouldered the burden of telling the stories of the downtrodden in the new millennium, a class whose numbers increase by the year, a fact that weighs on Springsteen throughout 2012's Wrecking Ball. Such heavy-hearted rumination is not unusual for the Boss.

Based on rating 6/10

Heavy lies the crown on Bruce Springsteen's head. Alone among his generation -- or any subsequent generation, actually -- he has shouldered the burden of telling the stories of the downtrodden in the new millennium, a class whose numbers increase by the year, a fact that weighs on Springsteen throughout 2012's Wrecking Ball. Such heavy-hearted rumination is not unusual for the Boss.

Based on rating 6.0/10

You've got to give it to Bruce Springsteen: dude is aging well. The 62-year-old rock legend has managed to stay relevant for his entire career, and his work ethic hasn't faded, at least not since that seven-year gap in records before 2002's The Rising. His albums may be uneven -- from the excellent We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions to the solid Magic to the troubling, slow darkness of Devils & Dust -- but he always seems to be behind his work.

Based on rating 3/5

No one really comes to a Bruce Springsteen album looking for subtlety. But there have been few Springsteen albums that so resemble a sledgehammer holding a megaphone as Wrecking Ball, his 17th. More rousing than The Rising, more polemical than his album of Pete Seeger sessions, Wrecking Ball deploys biblical imagery, train metaphors, Irish rebel reels, mariachi horns and even the sax solos of the late Clarence Clemons on an album in which the bankers get it in the neck so hard, some wags have already subtitled it Occupy NJ.

Based on rating 3/5

It's usually good news when Bruce Springsteen is angry about America, and that righteous fury over growing inequality and economic vultures is behind the best moments on Wrecking Ball. It's not technically an E Street album, but a track like We Take Care Of Our Own could fit in perfectly on Born In The USA and gives you the sense that the Boss is back. When he strays from that glorious wall of sound, things go awry.

Based on rating 5.9/10

"In America, there's a promise that gets made... called the American Dream, which is just the right to be able to live your life with some decency and dignity. But that dream is only true for a very, very, very few people. It seems if you weren't born in the right place or if you didn't come from the right town, or if you believed in something that was different from the next person, y'know..." With those words, Bruce Springsteen summed up his entire ethos-- searching for the American Dream and coming up short and then searching some more-- during a time of rampant unemployment and disquieting economic inequalities.

Based on rating 58%%

Bruce SpringsteenWrecking Ball[Columbia; 2012]By Jason Hirschhorn; March 12, 2012Purchase at: Insound (Vinyl) | Amazon (MP3 & CD) | iTunes | MOGThe Boss is often decried by his critics as trying to portray himself as working class, a sort of intellectual fraud. Despite being decades and millions of dollars removed from his blue collar New Jersey upbringing, Bruce Springsteen still chronicles the working class ethos and struggles he built his early career on, “Freedom son is a dirty shirt, the sun on my face and my shovel in the dirt” (“Shacked And Drawn”). While it is true that Springsteen is basically an actor, this isn’t something inherently wrong.

Based on rating 2.0/5

Bruce Springsteen’s transition from acidic everyman to sappy middle-class mediator has a clear demarcation point, a moment that at the time seemed like a career highlight. Nearly a year after 9/11, Springsteen released The Rising, a celebratory effort intended to bring a fractured nation together. And though such unity seemed like a possibility in the months after the tragedy, America became more divided than ever, riven by 10 years of war, social dispute, and economic crises.

Opinion: Absolutly essential

The leader of the free world returns with his 17th studio album. Ian Winwood 2012 On Easy Money, the second song on Wrecking Ball, Bruce Springsteen does as he often does: he licks the air and takes the temperature of the age. "We’re going on the town now," he sings, "looking for easy money." He then adds that "When your whole world comes tumbling down… all them fat cats, they’ll just think it’s funny." If in years to come seats of high learning devote degree courses to Springsteen’s work, there may well be a credit to be earned examining just why, when it comes to lyrics, there are no flies on The Boss.

Opinion: Fantastic

The characters in the songs of Bruce Springsteen have been through a lot in their time on Earth, almost 40 years now. They spent their youth loitering on street corners and burning down highways, in search of some promise of freedom that rarely came to fruition. Coming to terms with that disappointment was complicated by financial calamities and temptations that led them astray, and those who came through it OK became disillusioned when their American Dreams turned out to be lies.

Opinion: Fantastic

To the fat cats on Wall Street: Shill out that "Easy Money. " Meantime, Bruce Springsteen plays for the "Shackled and Drawn," "the blacks, the Irish, Italians, the Germans, and the Jews. " The Jersey Boss' 17th salvo stands as proof, a fiery hour written on behalf of all the saints and sinners working American soil since the credit system went bust and the housing market collapsed.

Opinion: Very Good

Here’s a thought: would Bruce Springsteen have fared so well critically had he been British? His lyrical mix of dirty realism and clock-card romanticism, his music’s blend of emphatic AOR and polished blues, the ageless crooning, the inevitability of finding one of his albums in a Volvo’s glove compartment: all of these are traits shared with Mark Knopfler and even Chris Rea, the would-be laureates of England’s own post-industrial rust-belt. Granted, neither Knopfler or Rea have explored the (relative) musical and political leftfield as Springsteen has, what with his Suicide and Pete Seeger covers and advocacy of liberal causes, and neither have made a record as brilliantly excoriating as 1982’s lauded Nebraska. This doesn’t mean, though, that there’s not occasionally a suspicion that Springsteen’s alternative cachet, at least in the UK, rests as much on his injection of a Transatlantic exoticism into the workaday as on the risks he’s taken from time to time.

Opinion: Fairly Good

The New York Times’s pop critics Jon Pareles and Jon Caramanica discuss Bruce Springsteen’s album “Wrecking Ball,” to be released Tuesday by Columbia. JON PARELES Jon, if good intentions were all that mattered, Bruce Springsteen’s “Wrecking Ball” would be a shoo-in for album of the year — which is, not coincidentally, an election year. “Wrecking Ball” is Springsteen’s latest manifesto in support of the workingman, and his direct blast at fat cats and banksters who derailed the economy.

'Wrecking Ball'

is available now